Walls made of stone blocks are not unknown in Bristol. Since medieval times the local grey Pennant sandstone has been a common building material, as in the wall shown below, which is situated in All Hallows Road in the Easton area.

Please note the second block down in the centre of the photograph; the purply-black one that isn’t Pennant sandstone.

It’s a by-product of a formerly common industry in Bristol and the surrounding area that only ceased in the 1920s – copper and brass smelting. Brass goods in particular were mass-produced locally and traded extensively, especially as part of the triangular trade during when Bristol grew rich on slavery.

Indeed it’s a block of slag left over from the smelting process. When brass working was a major industry in the Bristol area, the slag was often poured into block-shaped moulds and used as a building material when cooled and hardened.

Stone walls were frequently capped with a decorative slag coping stones, as can be seen below on one of the walls of Saint Peter & St Paul Greek Orthodox Church in Lower Ashley Road. Otherwise the blocks were just used like ordinary stone blocks in masonry as above. In some instances, the blocks have been used as vertical decorative features in masonry.

The finest example of the use of slag as a building material within the Bristol area is Brislington’s Grade I listed Black Castle pub (originally a folly. Ed.), where slag has been used extensively.

So if you see any slag blocks in a wall in Bristol, you can be sure it usually dates to the 18th or 19th century, more usually the latter, when Bristol underwent a massive expansion.

Moreover, these blocks are apparently referred to as “Bristol Blacks“.

There’s a link between Bristol’s brass industry and my home county of Shropshire in the shape of Abraham Darby I.

In 1702 local Quakers, including Abraham Darby, established the Baptist Mills brass works of the Bristol Brass Company not far from the site of today’s Greek Orthodox Church on the site of an old grist (i.e. flour) mill on the now culverted River Frome. The site was chosen because of:

- water-power from the Frome;

- both charcoal and coal were available locally;

- Baptist Mills was close to Bristol and its port;

- there was room for expansion (the site eventually covered 13 acres. Ed.).

In 1708-9 Darby leaves the Baptist Mills works and Bristol, moving to Coalbrookdale in Shropshire’s Ironbridge Gorge, the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution. In Coalbrookdale, Darby together with two business partners bought an unused iron furnace and forges. Here Darby eventually establishes a joint works – running copper, brass, iron and steel works side by side.

Below is the site of Darby’s furnace in Coalbrookdale today.

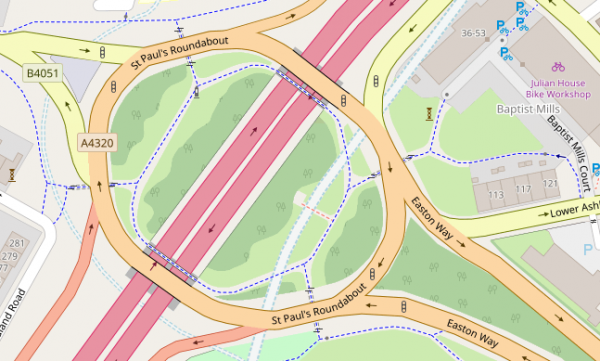

By contrast, here is what occupies the site of the brass works in Baptist Mills – junction 3 of the M32.

Thanks so much for such an interesting blog. It will make me look at walls with a keener eye!

It’s always worth looking for the unusual in the mundane, Hilary.

Bristol is not the only part of the country where slag has been used as a construction material. If you ever travel through the village of Redbrook in the Wye Valley between Chepstow and Monmouth – a former tin smelting centre – you may notice similar blocks in old walls.