Sydney Central railway station has many memorials, of which the most prominent is that to railway staff who lost their lives in war. It’s right in the middle of the central concourse up against the back wall.

However, there is another far less prominent one near the left luggage concession and Platform 1 that commemorates a war of a different kind, a war waged not against an aggressive or hostile foreign power, but on indigenous culture and heritage.

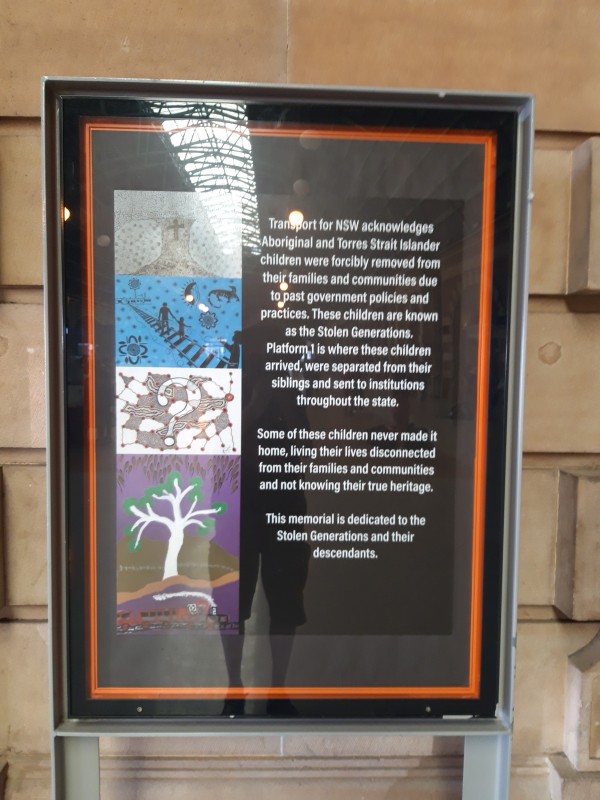

It’s very simple and consists of a grey metal frame containing a large panel of indigenous artwork and an inscription, as shown in the photograph below.

It commemorates the Stolen Generations, which Wikipedia describes as “The Stolen Generations (also known as Stolen Children) were the children of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who were removed from their families by the Australian federal and state government agencies and church missions, under acts of their respective parliaments.

The wording on the memorial reads:

Transport for NSW acknowledges Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children were forcibly removed from their families and communities due to past government policies and practices. These children are known as the Stolen Generations. Platform 1 is where these children arrived, were separated from their siblings and sent to institutions throughout the state.

Some of these children never made it home, living their lives disconnected from their families and communities and not knowing their true heritage.

This memorial is dedicated to the Stolen Generations and their descendants.

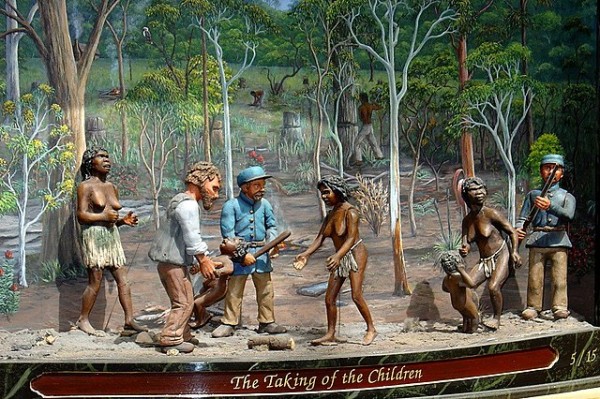

As stated in the station memorial, this removal was neither voluntary nor peaceful, as illustrated in the artwork entitled The Taking of the Children on the 1999 Great Australian Clock on the Queen Victoria Building (QVB), Sydney, by artist Chris Cooke.

The stated aim of the so-called “resocialisation” programmes was to improve the integration of Aboriginal people into modern [European-Australian, i.e. white] society. Nevertheless, a recent study conducted in Melbourne reported that there was no tangible improvement in the social position of “removed” Aboriginal people as compared to “non-removed”. In the fields of employment and post-secondary education, the removed children had about the same results as those who were not removed, but caused those involved great mental harm and trauma. A 2019 study by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) found that children living in households with members of the Stolen Generations are more likely “to experience a range of adverse outcomes“, including poor health, especially mental health, missing school and living in poverty. Among the Stolen Generations there are high incidences of anxiety, depression, PTSD and suicide, along with alcohol abuse, with the associated unstable parenting and family situations.

The federal states of Australia now all have redress and compensation schemes for the victims, but money is no substitute for not having suffered in the first place.

However, Australia is not the only country invaded by the British where indigenous peoples were maltreated. Similar indignities were suffered by First Nations children in Canada. In what looks like a very similar scheme, residential schools were created to isolate Indigenous children from the influence of their own culture and religion in order to assimilate them into the dominant white Euro-Canadian culture.

The same pattern can also be seen in Aotearoa (which some still call New Zealand. Ed.) in what Al Jazeera describes as a quiet genocide. More than 100,000 children – mostly indigenous Maori were taken from their parents and placed in state welfare institutions from the 1940s through to the late 1980s.

If these systems all developed independently, there does seem to be a lot of crossover – one might even say collusion – with trauma and loss of culture and heritage (and sometimes lives. Ed.) as the result.