The poorest he…

In 1647 during the English Civil War a series of discussions – the Putney Debates – was held in St Mary’s Church, Putney between 28th October and 8th November about the political settlement that should follow Parliament’s victory over Charles Stuart, the arrogant autocrat commonly referred to by history as Charles I.

In 1647 during the English Civil War a series of discussions – the Putney Debates – was held in St Mary’s Church, Putney between 28th October and 8th November about the political settlement that should follow Parliament’s victory over Charles Stuart, the arrogant autocrat commonly referred to by history as Charles I.

A transcript of the discussions can be found here.

The main participants in the debates were senior officers of the New Model Army who favoured retaining a monarch within the framework of a Constitutional monarchy, and radicals such as the Levellers who sought more sweeping changes, including One man, one vote and freedom of conscience, particularly in religion.

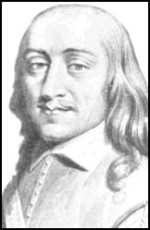

Amongst those Levellers whose words were transcribed is Thomas Rainsborough (pictured right), a colonel in the army, who is on record as favouring government by the consent of the governed, as expressed below.I think that the poorest he that is in England hath a life to live, as the greatest he; and therefore truly, sir, I think it’s clear, that every man that is to live under a government ought first by his own consent to put himself under that government; and I do think that the poorest man in England is not at all bound in a strict sense to that government that he hath not had a voice to put himself under; and I am confident that when I have heard the reasons against it, something will be said to answer those reasons, in so much that I should doubt whether he was an Englishman or no that should doubt of these things.Rainsborough was in particular supported by John Wildman and Edward Sexby. Sexby’s most salient contribution to the debates is as follows:

Our case is to be considered thus, that we have been under slavery. That’s acknowledged by all. Our very laws were made by our Conquerors… We are now engaged for our freedom. That’s the end of Parliament, to legislate according to the just ends of government, not simply to maintain what is already established. Every person in England hath as clear a right to elect his Representative as the greatest person in England. I conceive that’s the undeniable maxim of government: that all government is in the free consent of the people.

These sentiments were opposed by senior officers in the New Model Army, particularly Henry Ireton, and especially as they feared universal suffrage would remove the privileges that property ownership bestowed upon them.

In saying so, Rainsborough, Wildman and Sexby were men well ahead of their time, given the extremely limited nature of the franchise in those distant days. The franchise was not really increased to any great extent until the so-called Great Reform Act of 1832, which extended the right to vote (but still limited it by a property qualification) and abolished the so-called rotten boroughs. Even after the extension of the franchise, in a city the size of Bristol with a population at the time of over 100,000, only 15,000 had the vote. Working class men like my two grandfathers did not receive the vote until after World War One. At the same time the franchise was also extended to women over 30.

The incompatibility of monarchy with democracy was highlighted and put to good comedic effect by the Pythons in their 1975 film Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

You enjoy your bling bonnet day at our expense, Mr Mountbatten-Windsor, but just remember one thing: WE didn’t vote for you!