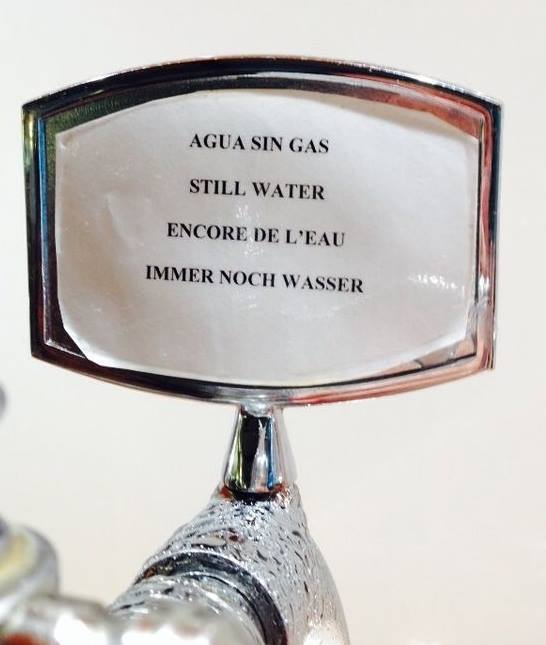

Another Google Translate classic?

No further comment is necessary.

No further comment is necessary.

Earlier this week Wales Online reported that train company Great Western Railway will not have Welsh language announcements or signs on its new class 800 fleet that will be providing services on the Great Western route from South Wales to London Paddington.

The lack of Welsh language announcements or signs on board was first spotted by Cardiff City Labour councillor and Welsh learner Phil Bale, who raised the matter with Great Western Railway via social media.

GWR responded to Cllr. Bale as follows:

I’m afraid we have no plans to have bilingual signage and on-board announcements on these services.

Diolch yn fawr, GWR!

The decision was justified by GWR remarking that the trains serve both England and Wales they aren’t a dedicated South Wales Fleet. However, as a patronising nod in the direction of Wales having a distinct language, GWR did point out that it had leaflets available in Welsh, but passengers would have to ask for them first (presumably in English. Ed.).

In response to GWR’s monoglot policy, Councillor Bales remarked: “For me it shows that Great Western are stuck in the dark ages. We have a Welsh Government target of one million Welsh speakers and there are international transport operators who manage to provide their services in different languages all across Europe.”

As the trains do serve both countries, one would have thought that providing bilingual announcements and signs would have been a common courtesy to those who speak Welsh; and as for Councillor Bales’ remark about running services in other countries, your correspondent doesn’t believe the travelling public overseas would tolerate the incompetence and sheer bloody-mindedness of GWR.

GWR’s attitude contrasts sharply with that of fellow train company, Arriva Trains Wales, which also runs services between Wales and England (e.g. from Cardiff Central to Manchester Piccadilly. Ed.). Arriva provides both signs and announcements in both Welsh and English, as well as bilingual ticket machines and timetables, even at English stations.

Plaid Cymru described GWR’s attitude as “disrespectful“, whilst a Cymdeithas yr Iaith (Welsh Language Society) spokesman said: “Ensuring bilingual signage and announcements on trains in Wales is a matter of basic respect for the Welsh language – there is no excuse not to. The fact GWR have said they don’t intend even to ensure these simple things, and that they’ve missed easy opportunities to do so, shows that they are not a suitable organisation to provide a train service in Wales.

“The Welsh Government should publish strong language standards in the transport sector so that the Welsh Language Commissioner can force companies like GWR to respect the language.”

According to the South Wales Argus, a Welsh Language Commission spokesman said: “Great Western’s alleged lack of investment in the Welsh language is a cause for concern.

“In 2016 the Commissioner submitted a report to the Welsh Government recommending that Welsh language standards should be placed on train companies. The Commissioner continues to work with train companies and others to develop the use of the Welsh language on a voluntary basis, and discusses public concerns with them.”

Yesterday’s Wales Online reports that Santander refused to deal with paperwork submitted by a customer… because it was written in Welsh.

Yesterday’s Wales Online reports that Santander refused to deal with paperwork submitted by a customer… because it was written in Welsh.

This is in spite of the fact that the bank has a clearly stated Welsh language policy which states:

We want all of our Welsh speaking customers to feel comfortable using Welsh language in their day to day banking with us and we encourage its use wherever possible. It’s why we support a number of Welsh language initiatives, allowing customers to use Welsh language in conversations with our Welsh speaking colleagues in branch, on our cash machines in Wales and when writing to us.

This policy was clearly not known to some manager somewhere in England as the bank declined to process membership forms after they were handed in at the bank’s branch in Aberystwyth.

After their submission in Aberystwyth, the paperwork clearly landed on the desk of a bank official who clearly didn’t speak the language of Hywel Dda, as the forms were subsequently returned to the branch in question with a note which stated: “Please return these documents to your account holder. Unfortunately Santander can only accept these documents written in English.”

Unfortunately, the paperwork in question was submitted to Santander’s Aberystwyth branch by Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg (aka the Welsh Language Society).

Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg’s rights spokesperson Manon Elin, commented as follows:

This is another example of a private company refusing to provide a Welsh language service because they’re not required to do so, and that’s completely unacceptable. We must have a language law which ensures that banks have to respect basic rights to use the Welsh language. Unfortunately, the Welsh Government’s plans for new legislation make it less likely that banks will have to comply.

The vast majority of people have to bank, but there is no means of banking online in Welsh, and we have to fight for other basic services in Welsh.

The society has also raised the matter with Minister Government Alun Davies challenging him to change the bank’s policy. In a recent white paper, the Minister refused to commit to extending Welsh language rights to the banking sector because of the ‘present economic certainty‘.

In response to this incident, the bank has commented as follows:

Santander accepts documentation that we receive in Welsh in line with our Welsh language policy.

We understand our customers who live in Wales may have various documentation and forms that will be written in Welsh.

If our policy has not been followed then we apologise for any unintentional upset this matter may have caused. The matter will be reviewed to ensure this does not happen again.

For your ‘umble scribe the final sentence from Santander can be translated into plain English as: “Oops! We’ve been caught out!” 🙂

In addition to being a chore, there’s now more than a hint of ambiguity in grocery shopping.

Take this sign in Tesco outlets.

Is it a threat or a promise? You decide. 😉

Hat tip: @soapachu.

In Britain many of the markets and fairs that survive today have their origins in the Middle Ages, when having successful markets and fairs could mean the difference between prosperity or oblivion to a settlement.

Where I grew up in north Shropshire, so successful was the market that the parish of Drayton in Hales – also known as Drayton Magna or just Drayton – tacked market onto front the name of the settlement and it’s been Market Drayton ever since.

The origins of Drayton’s market are indeed medieval and date back more than seven centuries.

In 1245 King Henry III (1 October 1207-16 November 1272) granted a charter to the monks of Combermere Abbey in Cheshire for a weekly Wednesday market in Drayton. That market is still held and draws visitors from a wide radius, not just from nearby rural villages, but encompassing urban conurbations such as The Potteries, a good 15-20 miles away. In recent years, the historic Wednesday street market has been supplemented by a Saturday market.

Over the centuries the original market changed of course. In 1824 the Buttercross was built, reportedly on the site of a vanished much older cross, in Cheshire Street as shelter for the farmers’ wives selling their dairy produce. When it wasn’t market day, the Buttercross was somewhere dry to leave the bike on trips into town.

During my childhood the general market was held in the middle of town in Cheshire Street and High Street, whilst the accompanying livestock market took place on a site off Maer Lane. I can remember helping to drive cattle to market through the streets.

The livestock market itself has not been immune to change. The site that I remember was sold off by its owners, local estate agents and auctioneers Barbers, who replaced it with new facilities out on the A53 bypass, rather further away from the town’s pubs, which used to open very early in the morning on market day.

In addition to the weekly market, there were also various fairs, one of the last of which was known as Drayton Dirty Fair. This was a livestock market which specialised in ponies and horses and was held in October each year.

An introduction to these fairs is given by Peter Hampson Ditchfield’s 1896 book, Old English Customs Extant at the Present Time: an account of local observances.

He writes:

At Market Drayton there are several fairs held by right of ancient charter. One great one, called the “Dirty Fair,” is held about six weeks before Christmas, and another is called the “Gorby Market,” at which farm-servants are hired. These are proclaimed according to ancient usage by the ringing of the church-bell, and the court-leet procession marches through the town, headed by the host of the “Corbet Arms,” representing the lord of the manor, dressed in red and black robes, and the rest of the court carrying silver-headed staves and pikes, one of which is mounted by a large elephant and castle. At the court several officers are appointed, such as the ale-conner, scavengers, and others. The old standard measures, made of beautiful bell-metal, are produced, and a shrew’s bridle, and then there is a dinner and a torchlight procession.

Let’s start with the Dirty Fair.

This was one of the last fairs of the year being held in October and its name originates not from the cleanliness of the attendees (which included a large number of gypsies and travelling folk. Ed.), but from the increased likelihood it being held in foul, i.e. dirty, weather.

When my siblings and I were children, our mother warned not to go near the Dirty Fair when it was on, which made it all the more attractive to we kids, of course. 🙂

To get an idea of the Drayton Dirty Fair in the early 20th century, I’m indebted to The Mercury (Hobart, Tasmania), whose morning edition for Thursday, 9th January 1902 states:

Quaint customs die hard. The ancient ceremony of proclaiming October or “dirty” fair, which dates from the thirteenth century, was recently observed at Market Drayton (Eng.). In the early morning the Court Leet of the Manor of Drayton Magna, consisting of the bailiff, aletester, constables, scavengers, searchers and sealers, chaplain, and town crier, paraded the streets warning all rogues, vagabonds, and culpenses, as well as all idle or disorderly persons to depart, or remain at their peril. There was no visible exodus.

The above account is supplemented by the mid-20th century memories of a Mrs Dorothy “Dot” Robinson, who recalls:

Every 24th October there was the “Dirty Fair” at Market Drayton when the gypsies from near and far gathered to sell their ponies. The ponies were put into fields around Betton Wood. They were almost wild but the children would climb on them and ride them. There were lots of caravans parked along the road especially near Mucklestone Rectory. They would collect tin cans from Daisy Lake, and make pegs. During the “Dirty Fair” there was a lot of drinking and fighting in the town so the children were not allowed there.

As far as can be ascertained, the last Dirty Fair was held some time in the early to mid-1970s. The Shropshire County Archives contain 3 photographs from the Drayton Dirty Fair; the last one is dated 1973.

When it comes to finding out more about the Gorby Market, the rural hiring fair held in Drayton and described by Mr Ditchfield, your correspondent has drawn a more or less complete blank. No etymological origins or other information has come to light despite weeks of searching.

The only other facts unearthed on the Gorby Markets were that two other Shropshire towns held them, i.e. Wellington and Craven Arms. The Craven Arms market mutated over time from a rural hiring fair to a more social event and died out some time in the 1920s.

However, there may have been many more hiring fairs than Gorby Markets. In his 1994 book, Shropshire’s Wonderful Markets, George Evans writes that hiring fairs, mop fairs and Gorby Markets were a common occurrence in most Shropshire market towns whose object was to hire out a man or a woman’s labour for a year, despite their various forms.

Besides the Dirty Fair and Gorby Market, Drayton boasted yet another annual event – the Damson Fair. In times gone by Market Drayton was reputedly famed for its Damson Fairs when the textile makers from the north of England would buy the damsons to make dye for their cloth. Damsons were used in the British dye and cloth manufacturing industries in the 18th and 19th centuries with large-scale planting occurring in every major damson-growing area, including Shropshire. In addition to northern cloth mills, damsons were also used as a dyestuff in the carpet and leather goods trades. This fair probably declined in the late 19th/early 20th century with the development of synthetic dyes.

If any reader can contribute to the gaps in my knowledge of Drayton’s Dirty Fair, Gorby Markets or Damson Fair, please feel free to comment below.

The latest example of this is the coverage of the appointment of Dr Patricia Greer by Bristol’s newspaper of (warped) record, the Bristol Post.

“New Bristol bureaucrat to be paid more than the Prime Minister“, thunders the headline in a piece posted yesterday on the paper’s website.

This is reinforced in the article’s first 2 sentences.

Bristol’s newest public servant is to be paid a whopping £150,000 a year – more than Prime Minister Theresa May.

The chief executive of the West of England Combined Authority will be paid more than double the amount received by her boss, Metro Mayor Tim Bowles.

First a bit of background: the West of England Combined Authority (WECA) is made up of three of the local authorities in the region – Bath & North East Somerset, Bristol and South Gloucestershire. North Somerset decided not to join in this additional level of local bureaucracy, but has said it will co-operate with WECA on transport matters.

WECA was imposed top-down by central government in the last round of so-called “devolution”. There was no referendum to legitimise its establishment, merely the usual inadequate consultation from the local authorities involved. WECA comes under a so-called “Metro Mayor”, the incumbent being Tory Tim Bowles who was elected in May 2017 on a turnout of less than one-third of the electorate.

Its detractors refer to WECA as Avon County Council Mk. 2, a reference to a previous unpopular round of local government reform.

However, to my way of thinking, the comparison of senior public sector employees’ remuneration with the Prime Minister’s pay is erroneous on a number of counts.

In the first place both Prime Minister and the Metro Mayor are elected offices: their holders find their way to their desks via the ballot box. WECA’s chief executive is appointed, presumably by a small body of individuals; the electorate has no say in who gets their feet under the big desk on the deep pile carpet.

Secondly, there are many appointed officers in the public sector whose pay is more on a level with those in the private sector. Take for example the large quantities of gold showered on the vice-chancellors of English universities such as Bath, which has resulted in resignations from that institution’s council.

Another comparison that could be taken into account is budgets. WECA will be receiving funding of £30m a year for 30 years, which is really just petty cash in public sector terms when stood next to the 2015 figure of running the NHS (£115,398m. Source: Cabinet Office).

Perhaps a fairer comparison would be with the PM’s senior civil servant, namely the Cabinet Secretary, the country’s most senior civil servant, who acts as the senior policy adviser to the Prime Minister and Cabinet and as the Secretary to the Cabinet. The post is currently held by Sir Jeremy Heywood, for which he receives an annual salary of £195,000.

Whilst this may be a fairer comparison, there’s one major drawback. Whereas most people could readily identify the Prime Minister when questioned, how many members of the public could readily name the Cabinet Secretary.

The media deal with certainties and the familiar, hence measurements related to the size of football pitches (and Wales! Ed. and, by extension, comparisons of those in high office with the PM’s pay packet.

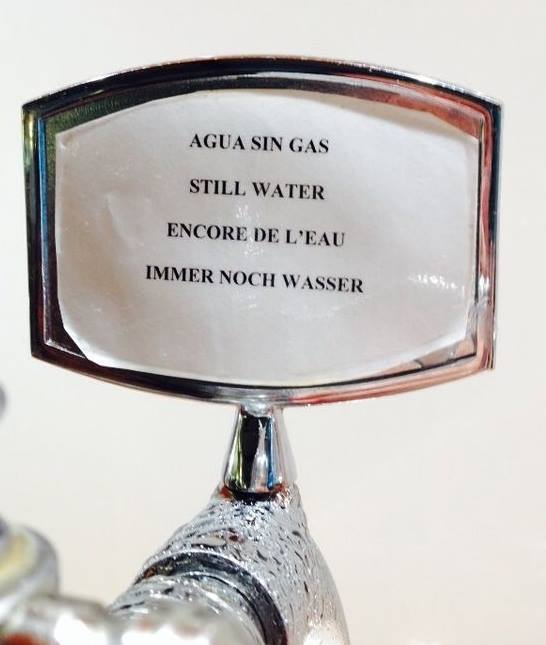

Social media platform Twitter uses Bing Translate, (another fine Microsoft product? Ed.), for tweet translation.

However, as this blog has highlighted before, Bing Translate isn’t all that good.

Indeed, for all practical purposes, it’s completely useless.

Evidence for this is legion. The latest in my timeline is shown below, where Bing Translate manages, with no external aid or interference, to confuse Somali, a Cushitic branch Afro-Asian language, with Estonian, a Finnic branch Uralic language.

This for me is reminiscent of the old Stork margarine advertisements that were doing the rounds in my childhood, where gullible television viewers were improbably told that the taste of Stork was indistinguishable from that of butter (or butter from a dead crab. Ed.).

According to an adage often attributed to Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw, it’s popularly said that Britain and the USA are two countries divided by a common language.

I’m therefore wondering whether for reasons of homophony (particularly in view of some British regional accents. Ed,), this forthcoming American film starring Jane Fonda and Robert Redford will be renamed for the British market… 😀

The shadowy East Bristol Tourist Board has recently been in action, welcoming visitors to Barton Hill, an ancient settlement recorded as Barton [Regis] in the Gloucestershire pages of the 11th century Domesday Book.

Barton itself derives from the old English ‘bere-tun‘ corn farm, outlying grange of barley farm.

From the visit of the Domesday assessors to the present day much has changed. The area still has one church, now St Luke’s, but the two mills mentioned in 1086 have long vanished. However, the area’s changes over the centuries – and those of surrounding districts – are being charted by the Barton Hill History Group.

This cheery message above can be found at the junction of Ducie Road (formerly Pack Horse Lane; there’s a street name that could tell a story. Ed.) with Lawrence Hill.

Have a nice day, y’all! 😀

Update 20/08/17: The cheery welcome message has now been painted over. Does this mean visitors to Barton Hill are no longer welcome? In the immortal words of Private Eye: I think we should be told!

Evidence that accuracy is not a priority at the Temple Way Ministry of Truth abounds every day in the online edition of the Bristol Post.

Below is a screenshot of the most egregious example of a lack of quality control in what passes for today’s local news since the title’s takeover by the quality-unconscious Trinity Mirror plc.

For those interested, the title’s sub-editors, the people that exercised quality control over what was actually published, were all made redundant many years ago. It is now up to the folk who write the copy to check it themselves.

That being so, your correspondent does wonder whether standards of English language teaching have declined in the five and a half decades since he first entered full-time education, or whether the teaching he received was of an exceptional quality.

If you have any thoughts about the quality of media reporting or language teaching, please feel free to comment below.